HARVEY SHANNON AND HIS RIDERS have pushed 550 head of cattle along a remote New Mexico two-lane for fourteen miles, descending 1500 feet in elevation and making a ten-hour day. Finally reaching the Dry Cimarron River, the men take their only break of the day, sprawling on the grass under a highway sign demarking the line between Colfax and Union counties. Horses and cattle show no interest in taking another step. For that matter, neither do the men, though there’s another full day’s ride ahead tomorrow, to winter pasture at Des Moines, New Mexico.

Harvey already knows they’re not going to make today’s goal, a “hotel pasture” just this side of Folsom. Instead he arranges with Sunny Hill, the rancher whose land they’ve just reached, to leave the herd up a box canyon behind her headquarters. It has a stream, grass, and steep canyon walls.

When Harvey rides in to bring them out at dawn the next morning, every last cow has disappeared. Another day of work begins.

HARVEY HAS BOUGHT AND SOLD CATTLE annually for 35 years, raising them on far-flung pastures that he leases. The leases vary over time from 10,000 to 80,000 acres, carrying 700 to 3000 cattle. “I owned a ranch at one time,” Harvey says. His parents had split the family ranch south of Kim, Colorado, along the New Mexico border. Harvey sold his share to his brother. “I was younger and more adventurous,” Harvey reminisces. “I tried to retire, for about six months.”

Back in his early days, Harvey had enlisted in the Navy, then used the GI bill to go to horseshoeing school; he was the only horseshoer in southeastern Colorado for years. He worked as a Colorado brand inspector, a bucellosis technician, and he vaccinated calves. During slow times, he hired on to do highway construction. “But,” he says, “it was ingrained into my soul to be a cattleman.”

“I KNEW THOSE COWS WOULDN'T STAY in that canyon, but I had no place else to put ‘em.” Riding up canyon, Harvey follows a trail of cow patties up a steep trail that looks more appropriate for mountain goats. Reaching the mesa at the top, he and his hands spend two hours gathering the herd. “The cattle change the rules on you. We can’t do it the way we planned but we can do it the way they want to and still get the same job done.” Harvey pauses, then adds with the hint of a grin, “Indecision is the key to versatility.”

He continues, “Most people think cows are dumb but they’re actually smarter than a lot of people. It’s easier to say they didn’t do something because they’re dumb than to say they outsmarted you. My dad told me when I was a kid, ‘A cow will do anything you want her to do as long as you convince her it’s her idea. But son, once you start taking that rope down to rope that cow, you have admitted that she’s smarter than you are.’

“My dad went on one of the last cattle drives from Clayton to Springfield, Colorado, around 1914, at age 16. That was a different era and they knew more about cattle than today’s cowboys do, because they didn’t have trailers. They had to be smarter than cattle, because they had to make cattle do what they wanted without forcing them.”

AT HOME IN DOWNTOWN DES MOINES, population 149, Harvey runs a tire shop out of his garage. There’s only a small sign, handwritten, on the door: “Temporary Hrs — 3:30pm – 6:00pm Aprox — Thank you. HLS.” Harvey’s talking into his cell phone outside the tire shop. “If nothing happens to the stock market, we’re gonna ship calves to Winters on the 27th.” The stock market was in a slide that would continue, steeper and deeper than the walls of that box canyon. Off the phone, Harvey explains that when the stock market falls, the futures market immediately follows, resulting in a drop in livestock prices.

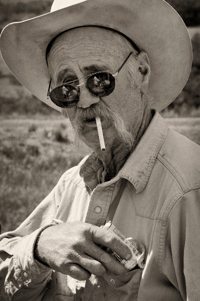

In other words, cattlemen watch the stock market. “The cattle business is one you become addicted to.” Harvey lights up. “It is more challenging than anything else in the world. It’s an addiction. It’s probably worse than any drug. It’s gambling at its best. You gamble your whole life savings on one year. You almost always get enough back to bet again.” Thinking back to the stock market, he adds, “You have to be a business person.”

Harvey muses on the toll the cattle drive took on the horses. “I watched a TV show once called ‘Extreme Horseman’ and just laughed because what I saw was nothing compared to what the horses here do every day.” He says he wore out horses three of the four days of the cattle drive. “They went lame – not hurt bad, but lame enough. One sprained on slick pavement, pulled a muscle. He started gimpin’ a little bit. The second one slipped and fell climbing the canyon. The third just got worked out, sore muscles.

“These are sort of the 4-wheel drives of horses, cattle-working horses in rough country.” Then, considering that this might end up in a magazine, he smiles and adds, “Don’t try this at home. Only professionals should try this.” A long pause. “No horses or cattle were injured or killed during the making of this article.”

FOLLOWING CATTLE WISDOM learned from his father a half-century ago, Harvey decides to leave the wayward herd at a large dammed stock pond atop the mesa, adding a day to the planned cattle drive. Rather than try to get the cattle back down the canyon they climbed, Harvey determines to move them overland, which will require crossing several ranches. He drives home to work the phones, calling the ranchers, all of whom he counts as friends and neighbors. He calls cowboys, assembling a well-seasoned crew. The next day, they drive the herd a final dozen miles to Des Moines, crossing eleven fence lines and passing under the afternoon shadow of Capulin Volcano.

The cattle safely home on winter pasture, Harvey Shannon rests his right leg across the front of his saddle and shares some laughter with the other cowboys. They’re already looking ahead. “Used to be it took too much time to do a cattle drive but now it’s back to the basics – we have more time than money. There’s no doubt we’ll do a reverse cattle drive next spring, to take them back up.” Harvey smiles at the thought, a gambler planning his next move, happy to be in the game.

©2009 Tim Keller