|

Words & photos © Tim Keller

A Note: I've begun writing short fiction sketches, using some of my own photographs as prompts. After discussing my intentions January 27 below, I began writing and posting these sketches. My regular blog posts begin with their dates, but the fiction begins only with a title, then the date of writing is posted below the story.

Charlie's Hat

A hat generation is shorter than a human generation. Charlie couldn't tell you how many stockman hats he's had over the years but, at 78, each one has been the same stockman style and size, 7 1/4, and always overlapped some months with the one that came before it. Why change.

The house has remained familiar as well. His family moved in when he was three. His kids live nearby with their own families--Charlie's grandkids--and Charlie lives alone in the family home. It's been home for 75 years. In the kitchen, he cooks and washes dishes with water from the hydrant just outside the door, the way his dad set it up in 1940. Why change.

He helped his kids build their houses. Theirs aren't the only ones that have sprung up here on the dry prairie south of town. Hundreds of houses are dotted across the low hills and along the twisting arroyos, making it ever more difficult for Charlie to move his shrinking herd of cows from place to place to graze.

Herd is too grand a word anymore for Charlie's cows. A few dozen cow-calf pairs is a big year for him now and, as droughts have become the norm, he rarely keeps so many. Buy 'em in the spring, ship 'em in the fall, and live on the profit from the weight they gain while you have 'em. Keep some mother cows over the winter to calve next spring.

Bigger outfits trade for a new pickup every three years or so, depending on the rain. Charlie's still driving his 1982 four-wheel-drive Chevy pickup. The cows know the truck from a distance when they see him coming along the winding two-track. He keeps three horses for cattle work but mostly the truck is all he needs.

A truck should last longer than a hat made of felt, subjected to so much sweat and dirt and weather. Making a hat last three years is, for Charlie, like making a truck last forty years. He takes good care of it. You care for your things as best you can. When their time is finally up, you reluctantly replace them. When they've suited you and worked well, you replace them with more of the same.

At the end of the day, you look back and appreciate the things that worked. You've made your bed and now you sleep in it. In the morning you choose the proven and the worn. They work. You work. Why change.

February 28, 2018

Lawn-Boy

If I do them in the same afternoon, I always mow the lawn first so it's not wet from washing the car. Actually, there are two lawns, front and back, and two cars, but I don't think I've ever managed to do all that in one day. That's why God gave weekends two days.

My dad backs the cars out of the garage for me, one at a time for the wash. My mom's gray 1964 Ford Falcon station wagon, and Dad's beige 1966 VW bug, about half the size of the Ford but I get the same three dollars allowance for washing it. I can do them every weekend if I need it, and mostly I do. I'm 15.

Dad had British sports cars when I was little. A Rover, then a Jaguar XK-120, then a Triumph TR-2. Now that his sons are teenagers, he has to be more sensible. Volkswagen bug. It's quick to wash but first I mow the front lawn. Today I'm rushing because I want to skateboard to school before it's too late. I gas up the mower and roll it out front. It takes three pulls, two coughs, and comes to life with an ear-splitting roar. There are two controls that extend to the handles from the body of the mower. I set the blades to full speed, the drive to mid-speed, and I make my first straight line along the curb, mowing the parkway before working up to the more irregular lawn where I have to curve around trees.

The more I mow, the faster I go. I increase the speed until it's maxed out and it's all I can do to keep up with it. At this rate I'll have time to spare when I finish. I pull the throttle lever and crank a turn at the hedge then quick push the throttle in a careen back across to the driveway. Except as I approach the driveway, there's my dad coming around from the back gate. He tells me to slow down. I can't do a good job like that. Slow down. He goes back through the back gate and into the house.

My spiteful streak emerges. I turn the speed control all the way down. Grandma could mow the yard at this speed. I could almost point it down the row and go wait for it to arrive at the other end. I'll show him. I hardly have to dethrottle to turn 180 degrees at the hedge. The machine and I creep back toward the driveway. My steps are the short shuffle of a 90-year-old man in slippers behind his hospital walker. As we slowly cross the walkway my dad catches my eye by opening the den window. I have to shut down the engine to hear him. He says I don't have to go that slow.

And I can't control myself. I break into a big grin, a big stupid grin, because I was running the mower stupidly slow, Grandma slow, out of pure spite, and I don't know what to do with Dad's reasonableness except grin and bear it. I want to go fast. I want to do it my own way. I don't want to mow at a reasonable speed. If I can't race unreasonably fast, I'll trundle along unreasonably slow. I'll show him.

Except, at the window, he's my father, and suddenly it returns to me how much I want to be like him. He's being perfectly reasonable, and I'm being perfectly stupid. It's hard to mow at mid-speed again, but I slog it out and finish. I feel ashamed, a lingering child today rather than the mature young man I want my dad to have for a son.

I wash and dry his bug, roll the hose and put away the bucket and towels. There's only an hour left before dinner. I pump my skateboard hard and fast all the way to school, where I have time for just two quick runs down the long steep hill. It's enough. By the time I get home the driveway is dry and the front lawn looks golf-course clean. I wash up and take my place at the table. I sit next to my dad.

February 11, 2018

Depot

Unmistakably a slam, the final closing of the door felt triumphant. There was nothing new about the argument and she was right, there had been no change. When suddenly I pronounced that I was headed out, it wasn't clear whether her heaves were grief or relief but my time was short and I packed quickly, leaving some books behind. The westbound train came through Hutch at three and I could easily make that, putting me in New Mexico for the sunrise of a new day.

Her final touch of kindness on the way out was no gift, only making it harder for both of us, but that's who she is. She's not going to throw something, and the yelling was over. No, now she asked me to let her know where I landed. Someday I'll probably do that but for now it's all forward motion, onward to the new, casting out the old. Motion is freedom.

The conductor said the sun will help melt the ice and the local crew will have the train back on its way in no time. It's almost as cold inside the depot as out but it's something to do, a piece of the west, the cost of exploration. I've no idea where I'm going. If my destiny was manifest I wouldn't be here this morning. Albuquerque will be warmer and more hospitable and my cousin always has a bed for me but it's no place to stay. I'll get my bearings and move on. Motion is freedom. The depot is cold.

February 8, 2018

Brothers in Arms

The kid won't stop squirreling around, thought Ben. How'd I get saddled with a brother that's such a goddam barrel of idiot monkeys. I'm supposed to do everything right, but him? There's the cowboy way, and there's the idiot cowboy way. From where I ride, he's always trouble. Always. I'd like to slap him around but then Pa slaps me around. Every time. Pa never slaps him around cause he's the kid. No matter how fast he grows out of crap, I'll always be two years ahead of him and it'll never be enough.

Ben just sits there all serious, thought Jared. Always all serious. I wanna slide a racer snake down his shirt just to get a rise out of him. Wrestle or chase each other across the goddam field throwing things this way or that, mix it up. He's a better hand than me but how am I supposed to top that? Every year I live, he's still gonna be two years older. I'm Pa's free spirit, the Department of Fun. Somebody's gotta be in charge of fun around here and it ain't gonna be Ben. I'm in charge of frog gigging and sneaking ice cream. That's my territory. He's humorless. That's what he is, humorless.

Last month Jared sat a colt, Ben recalled, and if I hadn't been there he could of got hurt bad. Pa says that's part of my job, to take good care of Jared and help him grow up right. He got scared on the colt and that's a good sign. Shows he has a little sense anyway. When I got him down he hugged me. Sometimes it's like there's a hobble tied from my ankle to his, like I gotta drag him around or keep him from running off. I swear, you don't keep an eye on him, no telling where he'll end up. Give him five minutes and you'll wish you didn't.

I wanna race, thought Jared. If Ben won't race me, maybe if I jump out of the truck I can cut across the pasture and beat them to the corrals. The two-track curved around to hug the thin treeline along the arroyo before reaching the horse barn and corrals. Jared suddenly threw himself over the rail of the pickup bed and raced across the field, the happiest man in the county, the Department of Fun, his laughter racing out two steps ahead of his little boots.

February 4, 2018

The Glass

He's done drinking before midnight and gets a little sleep. Even in the best of times he never slept well, though with her he'd stay in bed all night just for her company. There's always lots to think about. There was enough to think about that she left.

The passage of time. The lack of...purpose? direction? point? There's nothing to do about it but think, and drink, and that passes the time, slowly, slowly. The prospects for change are not high, no bright sunshiny day coming around the corner.

The glass is neither half empty nor half full. It's just a glass. He walks two blocks to the club to face each sunrise from deep in shadow, as though daring the first horizontal rays to reach as far as he has gone. Same as the others, it's a new day.

February 2, 2018

The Money

Nah, they're just here to dabble with cowboys, play cowboy once a year. A couple of them even get on horses for a picture, though it's better to do that before they get too far along in their drinks. They come down from Orange County, some of them from LA, to get a little dirt on their jeans. Last year one of them had his picture taken holding the iron over a bawling calf's flank, big cowboy. Then he put the iron back on the fire, freeing up his hands so he could get his cigarette and beer back from his wife. You best just keep working, kid, and ignore the money if you want to stick. Come Monday morning, it's all they'll be talking about at the office, and you'll be out in the muck at the cow camp same as last Monday. Don't you just love it? I know you do.

February 1, 2018

(Note: This is the 1967 roundup at Rancho Mission Viego out the Elsinore Highway east of San Juan Capistrano, California. Also known then as the O'Neill Ranch, with 53,000 acres, it was my first job; I was 16. And no, the kid in the sketch isn't me: I was building fences and the like, general labor, not mucking with cattle. My ride was not a horse but a Ford pickup, and I usually rode shotgun so it was me that had to get out to open and close every gate.)

Coyote

The rain hadn't made the drive any easier. Four hundred miles, that's a thing but not a hard thing. They'd done it before, no problem. Jerry always drove, and Ray had long ago stopped cracking the passenger window because it irritated Jerry. They got along. Except today, well, maybe it was the rain.

You just haven't done well with women, Jerry offered. Well with quantity, he clarified, but not well with quality. The keepers walk right over you and they're the ones that stick for years.

Next one I'll run her by you first, Ray said. What difference does it make to you. It's got nothing to do with you.

We'd see you more often if we liked your women. And we like seeing you, despite yourself.

The turnoff to 26 is coming up on the right, Ray said.

Rhonda's got you on a leash. It's a long leash, I'll grant you, but she keeps you circling, Jerry said. She's a neighbor with benefits.

I'm not a dog, Jerry. I'm a coyote. I make my own moves and go where I want. I'm here with you aren't I. Rhonda's cool enough. And I'm a free man. I'm a coyote.

You used to be a wolf so I'd say you're downsizing.

Jerry veered right onto 26 and the rain picked up again. Ray cracked his window. They weren't far now.

January 30, 2018

The Green Apple

The camper sat there for several cat lifetimes. One cat lifetime ago, Saunders moved into it. He painted it green to mark the occasion, figured if he was going to live in a shell, at least it'd be spruced up and lively. A couple days later, weeding the garden, he named the camper The Green Apple. No one else ever knew this. It's not like he had a lot of friends anymore, or told anyone at the store that his camper was named The Green Apple. He told the cat, and after that one died and he took in Rosie, he told her, but cats don't tell.

Like the others, Rosie started wild, a feral cat from under the big sheds on the adjoining property. Like the others, she grew tame under his influence. He had a place under the table where he kept bowls with water and cat food. Rosie took to sleeping with Saunders at night, usually nuzzled against his legs for warmth. Most nights she came in on her own accord, mewing at the door. Saunders listened for her each night and worried when she was late. Sometimes she wouldn't come and he'd fall asleep worried. Around midnight she'd show up and the small mewing outside his window was enough to wake him because he was waiting for her. As his health declined, Saunders wished some days that Rosie would come around more in midday to keep him company.

One September night Rosie came home to The Green Apple but Saunders didn't open the door. She scratched at the door. She waited. In the morning she was still waiting. She looked up at the window where they slept. She waited.

January 29, 2018

Arugula

The chair scrapped along the pine floor as she pulled it out to offer it. The napkin rings and red carnations had been a tough call, maybe too much. He'd taken his hat off and left it at the door. That got her attention, rancher boy, impressive that he didn't leave the hat on. He ran his fingers through his hat hair, roughed it up. Faint smell of wind, grass, cows. Awkward inside, in town, at lunchtime.Two Saturdays at the farmers market, two flirtations, and now a town lunch on a Tuesday of all things.

She had her hair tied up with a red ribbon, matching the flowers. She set the two salads next to the iced tea she'd sunbrewed in the second-floor window. He chose the ranch dressing, she the vinaigrette. This is a different kind of lettuce, he said. Kinda bitter. It's arugula, she said. Like Obama, huh? He didn't know arugula. She said it's lettuce. She got it at the farmers market, remember. A car horn below the window helped change the subject.

Yes, she said, she liked living downtown. He couldn't do it, he said. He had to park his truck two blocks away and walk. She'd heard his boots on the stairs. Maybe she'd come out and see his place sometime. How would her Prius do on the dirt roads, she asked. Depends on the season, he said, but yeah, that could be an issue. Maybe I could pick you up.

She brought the sandwiches and he was relieved to see bacon. He thought there might be more arugula. Good old-fashioned BLTs except the bread was fancy. The lettuce was lettuce, not arugula, better. He asked for sugar for his tea. How long had she been living here, he asked. She moved from Houston in September, made it through her first winter. She was more a summer girl, but being downtown made it easier. She was glad for the summer.

He was, too. It was his busy season but less mucky and he made a lot more money. His truck got new tires last week. He didn't get to town more than a couple times a week, usually midday or night. Early morning and late afternoons were the busy times for work, when he had to be on the ranch. She was more flexible, she said, working out of her home office, with a window looking to the mountains in the north. Sometimes she worked all night. Sometimes she took the afternoon off to go to the museum.

She brought a plate of cookies for dessert. I made them this morning, she said. No arugula in them, he wondered. She laughed. Finally. No, walnuts and chocolate chips. Old fashioned, he said. I'm old fashioned enough, she said. Like the red ribbon in your hair, he said. She smiled. What was the rest of his day like, she asked. I've got to get my buddy and two horses, he said. We're moving some cows from one pasture to another and it's a ways. We'll be lucky to finish and drive home before dark. In fact, I need to get a move on, don't I.

She enjoyed the sound of his boots going down the wood stairs. She stacked the plates in the kitchen and set the red carnations in the open window. The street sounds below grounded her. She wondered if that was his truck going by. It turned right, to the south. She walked to the mirror to look at the red ribbon in her hair. It looked just right.

January 28, 2018

January 27, 2018 Cruising Paradise

Sam Shepard was best known as a playwright, winning the Pulitzer Prize at age 36 for his play Buried Child; he was also famous as an actor. He traveled extensively but didn't trust airplanes so he spent a lot of time in cars, trains, and motels; much of that time was spent in the American West. Often, he traveled alone and carried a typewriter. The products of that typewriter would be published, beginning with Hawk Moon in 1973, as stories, tales, poems, and monologues. The fifth collection, Day Out of Days, arrived in 2010. While some pieces ran as long as 16 pages, most were very short--just a page or two or three--the length, I think, he would write spontaneously in one sitting, perhaps in a motel room in Winnemucca, Nevada.

Since my retirement from teaching almost three years ago, and semi-retirement from professional writing and photography that I've been transitioning into, I've been pondering what to do with my blogs. They used to be commentaries on the various projects I was doing. They can still be that--I remain active, though I'm no longer pitching stories to editors--but Shepard's short pieces have lately been inspiring me to try his approach here. I doubt that he sat down with a planned piece: I think he sat down at the typewriter, chose the kernal of an idea, and wrote his way to a tale. A sketch in words. That suits me well right now. I don't want to tackle big projects, but I love to write. I love to type, as I'm doing at this moment. ("Keep typing until it turns into writing" -- David Carr.)

Look at Shepard's portraits above on the covers of his books of plays--the intensity on Seven Plays (1981) versus contentment on Fool for Love (1984). I see my pre-retirement self in the first and my post-retirement self in the second. Most of all, I love this last photo (with his Lexington Herald Leader obituary last July) from late in Shepard's life, playing a mandolin. His intensity and intellect still show, but so does his relaxation and age. Shepard has inspired me since 1984 (see "January 10, 2018: Written in the West" at the bottom of this page), and even now in my late 60s, he remains a role model.

So, while I'll stay close to photography at my companion TKP Blog, here at this broader TKA arts blog I'm fixing to include some writing that is more creative and experimental. As visually oriented as I am, I still hope to include at least one of my own photographs in each post, even using them as jumping-off points, kernals to begin the writing--something Shepard did occasionally, too, including a photograph with a story. Some, many, of the pieces won't work, no doubt, but I'll be enjoying the writing. Once in a while, I'll hope to spin off something that both you and I enjoy.

comment

January 25, 2018 Eagle Tail

Our home at Raton, New Mexico, is blessed with beauty in every direction. The Rocky Mountains reach into the westside streets almost to Main Street--which here is 2nd Street, just above Historic First Street adjacent to the railroad. Behind our northside house is Bartlett Mesa, the first of three mesas to the east--Bartlett, Barela, and Johnson--that lead into the Clayton-Raton Volcano Field, more than 100 volcanoes in a 60-mile radius east of Raton, studding the beginnings of the Great Plains, magnificently visible from Raton.

Southeast of town, just east of I-25, lie Tinaja Mesa and Eagle Tail Mesa, two majestic landmarks along the old Santa Fe Trail. Once our high-mountain trails get covered in snow each winter, I spend those months hiking on a big horse-and-cattle ranch down by Eagle Tail where snows melt away quickly. (Our mesas and mountains top out at 8000 feet, while the surrounding plains are at 6000 feet; our house is at 6800 feet.) Our border collie, Django, and our Jack Russell Terrier, Jett--both rescue-dog mixed breeds--live for our afternoon hikes.

We've developed a basic ranch loop hike of 5.5 miles that takes us 100 minutes, though sometimes we loop wider to get seven miles, or we can have a short hike by simply hiking down the two-track a ways and then turning back, something we do if the windchill factor is in single digits after a winter storm. We drive 14 miles from home, with eight of those miles on a county dirt road, so it's not worth going at all if it's too cold to hike far. Most winters, that happens a few days per month, but this year it hasn't happened yet. We've had very little winter--great for hiking, bad for the land, planet, and people.

This week we were gifted with a natural phenomenon that I don't remember ever seeing: The sun sent down a strong beam of light, like a light sabre. Jett, in a pair of photos above, was as taken by it as I was. I pulled out my iPhone 7 (my hiking camera) and took several photos. The sunbeam seems to land directly on Jett's shadow, on his head and heart as he shifts position to look at it. (As always here, click any image to enlarge it.)

Magic? Magic is not uncommon around here. We live in a magical place. I'm just sayin'.

comment

January 19, 2018 Tom Noe -- Renaissance Man, Friend

Tom Noe died this morning. He stayed up all night, in his easy chair, and then, as the sun rose, he left.

He'd been ailing and was ready to go, his way. He wouldn't go to the hospital. His decline came too fast, the last couple years, and he was too young, just into his 70s. Until last year he was still stopping by for an annual overnight visit on his motorcycle commutes between Texas and Seattle.

Tom was easily one of the two or three most fascinating people I've known, and for exactly thirty years he's been one of my best friends. I can count my best friends on my right hand and have enough fingers left to make a peace sign, but for Tom to count his best friends would have required all his fingers and toes and then some extra sets.

Thirty years ago Christina and I were living in a rent house on a remote 10,000-acre ranch between Santa Fe and Las Vegas, New Mexico. Late one night our phone rang, always a little unsettling. It was a guy calling from Santa Fe, said I'd given him my number at the Kerrville Folk Festival, he was traveling and asked if he could stop by. At 11 p.m. a big motorcycle pulled into our dirt drive, initially a little alarming until we heard its stereo speaker blasting a song from my first album.

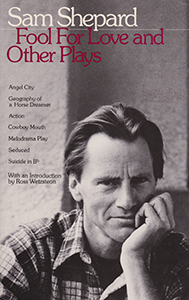

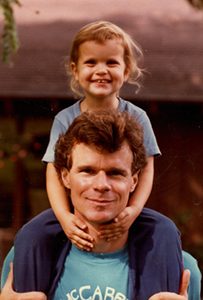

Tom returned every year, usually on a motorcycle. He took my daughter Darcy on a ride down the road and back, then she and I clowned on his bike for a picture. Nine years ago I blogged here about Tom's visits in Des Moines, New Mexico, and his influence on our photography, both mine and Christina's.

I'd have to write for days and days to adequately convey Tom Noe. Born and raised in Kentucky, he spent much of his adult life north of Wylie, Texas, initially a rural area north of Dallas, in a house he built himself. An engineer, he made a fortune for Texas Instruments, if not himself, before leaving to be an independent entrepreneur. He invented a photo processor that allowed small organizations--police departments, newspapers--to develop their own few daily rolls of photographs. He had ten full-time employees in his small manufacturing plant when I worked a couple weeks for him: A touring musician, I needed every dime I could get. I'd book myself a week of gigs in Dallas, then work days for Tom. (In those years, Tom had a mixed-breed dog named Sport who would accompany him to work each day, riding behind Tom on the motorcycle to the turn from the highway, then leaping to the ground and racing across the block to easily beat Tom to the door.)

Tom was both a motorcycle nut and telescope nut, but good telescopes were too big and heavy to carry on his bike. He invented a portable telescope good enough to take him to the Whirlpool Galaxy; he called it the Teleport. He closed his photo processor business and built a big new shop next to his house where for many years he built Teleports; he also continued to make replacement parts for his former photo processor customers. His Teleport customers grew to a three-year waiting list. On the way home from a star-watching party in eastern Washington about 14 years ago, Tom and his wife Linda stayed with us on land we had out in the country here in the northeastern corner of New Mexico. They were amazed that our night sky was as dark as eastern Washington, and much closer. Tom came back a month later to give us an early prototype 10" Teleport and taught us how to use it. Two years ago, Tom insisted on picking it up here, took it home and refurbished it, bringing it up to his current standards, even adding a new set of eyepieces for which he spent several hundred dollars, then he returned it to us. (Finally curious about its dollar value, I asked. Tom guessed it would bring about $4000 on Ebay. We're keeping it.)

For years, Tom ran a popular house concert series, more than 100 concerts of touring singer-songwriters and other folk musicians. I was proud to have been the first. Tom enjoyed singing and playing guitar. I was proud that he asked me to teach him my songs "Across the Borderland" and "Fence Me In," which he occasionally performed for us over the years. Tom was instrumental in getting me started on computers, helping me move my touring schedules from typewriter to computer. He was always brimming with ideas--he'd leave books for us to read--and stories and photos of his travels. He and Linda spent the last ten years building a home on the Kitsap Peninsula by Puget Sound near Seattle, which benefitted us because they'd stop overnight and visit as they commuted to their summers in Washington, where they finally moved full-time last year.

Last night Christina gave me a dire warning that Linda had posted to Facebook about Tom. This morning Linda posted more. "He was more than ready to go...He didn't want to die in the hospital and asked me not to call 911. He said there was no specific pain but breathing was very difficult."

Linda held his hand and talked with him until first dawn, then went to get a couple hours sleep. "When I woke up about 8:30 he was gone. He died in his recliner with a glass of scotch at hand."

She continued, "We'll cremate his body here, as he wished. There are several places he wanted some ashes scattered."

Goodbye, Tom. You are sorely missed.

comment

January 16, 2018 Pork Futures

Driving backroads around the Kansas plains, mostly all you see is wheat or, in January, empty wheatfields. Or stubbly corn fields. The occasional center-pivot irrigator parked in a field, or a big storage garage alone amidst miles of fields. Driving south from Scott City on Kansas 25, a paved two-lane highway, my eye was attracted to a long row of low gray structures along the horizon a mile west. Turning down the gravel road that led there, I found what looked like two matching concentration camps--seriously, two World War II German concentration camps--a mile apart from each other down this dead-end road many miles from the nearest people--the nearest ears and noses, because it turned out to be pork processing plants. As I photographed a wide panorama from several hundred yards east, I could hear the squeals of pigs.

Like "Hogan's Heroes," the owners are not without whimsy: the business is called Huff & Puff Pork LLC, although right under the name on the sign is the bold red warning: "No Trespassing - Security Cameras On Site." On this vast sprawling site, there were only two older pickup trucks at one of the buildings. On the second site, a half-mile farther, down at the road's end, there was only one pickup truck. (In contrast, the enormous Tyson plant at nearby Holcomb had several hundred vehicles parked in sprawling lots day and night.)

I found the scene mystifying, though the signs kept me from exploring closer. If I was working on a story, or even a travelog for a magazine, I would have sallied forth and talked to whomever was up there. As it was, I was just a semi-retired photographer out on a photography road trip. A bacon-eating, pork-rib eating photographer, although all the monstrously huge meat-processing plants (beef, chicken, and now pork) I saw around Kansas gave me pause and made me glad that I live where I can largely avoid industrial meat by buying from a local farmer. From the Goebels in Maxwell, thirty miles from our house, we recently bought a lamb--which dressed out to one large cooler of frozen white packages of meat--and a quarter of a beef, two large coolers of frozen white packages. Around here, many people keep an extra freezer for storing local meat. After Huff & Puf Pork LLC, it makes my conscience feel a little cleaner.

comment

January 14, 2018 Father and Son

That's my ride. It's a 2017 Porsche Cayenne S, custom ordered from Germany. My dad and I bought it last year. He always loved sports cars and owned a Porsche 914 for a while after I finished college. He died at the end of 2016, and I bought this Porsche with his money. He was too sensible to spend his money on sports cars--he left behind only his 2002 Honda Odyssey van, with 37,000 miles on it--so I did it for him.

My dad, Jack Keller, was a photographer, too. Until I came along, his first born, he was trying to make a living as a photographer. Growing up in a photographer's house turned me into a photographer. And a sports car enthusiast. For years Dad took me to the Riverside Gran Prix each October, where I got to see legends like Mario Andretti and Dan Gurney race around the three-mile-long nine-turn track. Late one afternoon after the race, on our way out from the infield parking, my dad even made a right turn down the mile-long back straight and took a full lap in his Triumph TR-2. Later, my first car was a used Triumph TR-3A, bought with my own money ($600, a summer's wages) earned working as a ranch hand, at age 16, at Rancho Mission Viejo where my dad's dad, George Keller, worked as the company purchasing agent.

Dad's been gone more than a year now, but driving around Kansas in our Porsche, carrying Nikon cameras on a photographer's solo road trip, I couldn't be happier...or feel more in touch with my dad. I turned from photographing the sunrise over the frozen Arkansas River at Holcomb to catch the sun under the Porsche. Magical moments like that, they happen all the time. The road is long, the turns sweet, the memories, photographs.

comment

January 12, 2018 Holcomb, Kansas

When playwright Sam Shepard wrote a script for filmmaker Wim Wenders, it led to a film that propelled me into Shepard's fractured characters and landscapes. This month, his Motel Chronicles and Wenders' Written in the West images propelled me to a photography road trip. I wanted new ground but not too far away, and not north--it's winter, after all, if a mild one so far. Rural southwest Kansas met all my criteria. And, for more years than I can remember, I've wanted to see Holcomb, Kansas, and the Clutter farm, site of the November 15, 1959, murder of Herb and Bonnie Clutter and their teenaged daughter and son in their house in a botched robbery late that Saturday night.

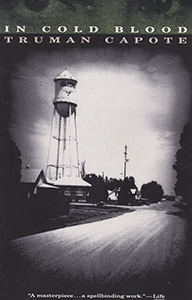

Neither I nor you would have ever heard of tiny Holcomb, Kansas, but for this horrific crime, and we wouldn't have heard of the crime or the little farm town if it wasn't for Truman Capote's extraordinary "non-fiction novel," In Cold Blood. I came to Capote through literature, and a fascination with his and Harper Lee's Alabama childhood together as fictionalized in her To Kill a Mockingbird. Though I'd seen the 1967 film version of In Cold Blood, filmed in Holcomb itself and the Clutter house, it didn't resonate until I finally read the book years later (and then again in 2015). It's Capote's prose that excites.

The competing 2006 films Capote and Infamous tell the same story of how Capote conceived a novel made entirely of true material, not fictionalized but told with the dramatic impact and construction of the novel. The former, starring Philip Seymour Hoffman as Capote and Catherine Keener as Lee, is perhaps a bit better than the latter, starring Toby Jones and Sandra Bullock, though I like both films enough to revisit them periodically. Funded by The New Yorker, Capote rushed to Holcomb from New York the day after the murders got a small notice in the New York Times. Off and on, he spent years in Holcomb, often accompanied by Harper Lee as his friend and research assistant.

In their jail cells, Capote befriended the ex-cons that murdered the Clutters, interviewing them extensively, and he kept coming to Kansas until he had the end of his novel--the 1965 hanging of the two murderers. The process changed, and damaged, Capote. He knew he'd created his masterpiece, but he couldn't finish or publish it until the killers were executed; meantime, he kept visiting them. He witnessed their hanging, then finished and published In Cold Blood. He didn't publish another novel during his lifetime; he died in 1984, shortly before his 60th birthday.

It was easy to learn the location of the Clutter house and farm online. I photographed it at sunrise on my first morning in Kansas. The fractured, nonsensical events of November 15, 1959, could have made a Sam Shepard-Wim Wenders movie. Truman Capote got there first. He says six people died as the result of that night, but it gradually brought him down, too. Left behind are a great book, some great films, Holcomb and the Kansas plains.

comment

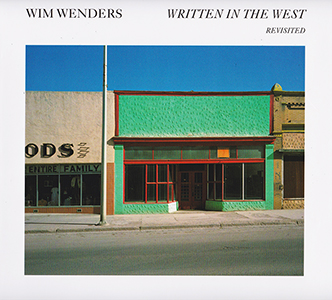

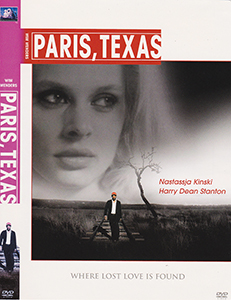

January 10, 2018 Written in the West

Like many Germans, filmmaker Wim Wenders grew up enamored of the American West. Thirty-five years ago, when my daughter was a toddler, Wenders teamed with American playwright, actor, and Westerner Sam Shepard to create the film Paris, Texas. Shepard, who died last July, was well known for shunning airplanes and constantly traveling the US by car and train. In preparation for making their movie, Wenders came to America and spent months driving around the remote corners of the American West, alone with his large-format film camera. This visual journey influenced the shots in the film he directed, and he later published Written in the West, a book of his western still photographs. Revised, "Revisited," and re-issued in 2015, I received a copy last month as a birthday present from my daughter, who knows those Western landscapes fairly well by now.

Shepard made a lifelong habit of such western wanderings, carrying a manual typewriter in place of Wenders' camera. Shepard didn't turn on the motel TV; he typed something in most motel rooms he visited, publishing five books of those writings during his lifetime--mostly short tales and some poems. The second collection, Motel Chronicles, overlapped with Wenders' western wanderings and with Shepard's writing of the script of Paris, Texas, which explores the disintegration of everything above ground in the modern West, including buildings, signs, and human relationships. I didn't know Wenders or Shepard when the film came out in the summer of 1984 but I was drawn by the Western landscapes and subject matter.

The film shook me to my core. I was a newly divorced father (right) visiting my family in LA when, one afternoon, I left Darcy with my mom so I could go to a matinee at the Wilshire Theater. I still remember driving the 10 back to Pacific Palisades after seeing Paris, Texas, disoriented and emotionally unstable. I'd loved the milieu of the film--still do many viewings later--but the inability of the protagonist, Travis (played by Harry Dean Stanton), to hold his little family together hit too close to home. I conflated him with me, his son Hunter with Darcy. Coincidentally, in both cases the father and child were in LA while the mother was in Houston--but the disturbing parallels ran much deeper than that. Like Travis, I was devastated by my inability to give my daughter a whole nurturing family. To this day, I turn to tears in a heartbeat when these feelings are triggered by a movie, a book, or life. The parent-child relationship slays me.

I remained peripherally aware of Wenders through his later films--Wings of Desire, Until the End of the World, Buena Vista Social Club--but Darcy and I were still in LA that summer of 1984 when I bought a biography of Shepard (who was then only 40, already a Pulitzer Prize winner) to try to wrap myself around his Paris, Texas story and understand his fractured narratives and people and worlds. I saw the film again right away, then again and again. I bought and read his plays. I'd moved to Santa Fe that spring. In the fall, the wonderful El Paseo theater (now a western clothing store near the plaza) hosted a weeknight premiere screening of Paris, Texas. Co-star Dean Stockwell addressed the crowd. Sam Shepard was there--I'd seen him slip throught the lobby into the theater, incognito--but he wasn't announced and didn't speak.

Jump forward these decades. Shepard died at his Kentucky horse ranch late last July; he was 73. (Harry Dean Stanton died six weeks later.) Wenders has reissued his book. Darcy and her filmmaker husband have moved from Brooklyn back home to Austin, where they'll be welcoming a baby girl in April, making me a new and happy grandfather. They sent me Wenders' book for my birthday and it triggered so many connections and memories (that cover image above, for example, is a storefront on Bridge Street in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where I lived later in the 80s and still visit regularly) that it provoked sudden wanderlust. Now that I'm retired, I largely get to do what I want, when I want, so I went, out into the West alone with my camera. I wandered around southwestern Kansas last week taking pictures for three days, long enough to bring home photos (above) and thoughts that will keep me busy the rest of the month creating blog posts here and at my photography blog. Time heals only partially, leaving scabs that turn into scars, and the struggle against disintegration continues unabated until, like Shepard, we finish. Meantime, what we have is life. I find it worth every ounce of persistence. Worth every tear. In fact, if I may blather here, it's goddamn magnificent.

comment

Tim's Blogs - Archive |